On a clear day at Sleap (pronounced ‘Slape’), north of Shrewsbury, the watch tower (aka control tower) looks almost ordinary: a blunt, square marker from the wartime landscape, the sort of building that has outlived the urgency that made it. Yet it carries a reputation that refuses to fade. People still talk about the RAF Sleap control tower as “haunted”, a place where the past doesn’t so much sit quietly as press back, particularly after dark.

That reputation isn’t built on thin air. In late summer 1943, within roughly a fortnight, two Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys struck the control tower/watch office during night training. The second collision killed not only aircrew but also WAAFs working inside the building. You don’t need a taste for ghost stories to understand why a site like that would gather folklore around it.

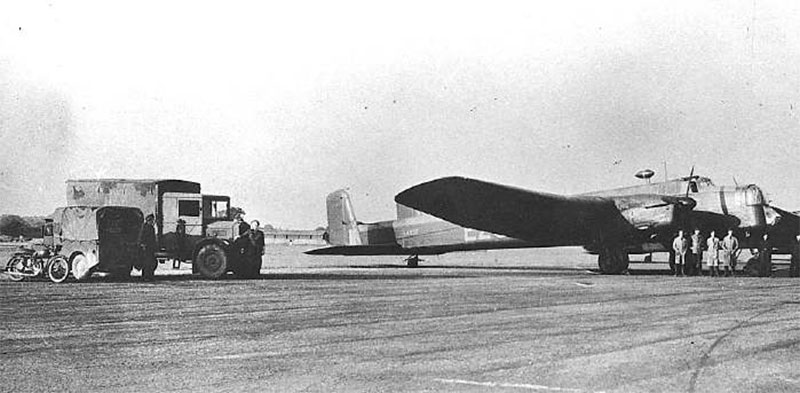

RAF Sleap airfield history

RAF Sleap opened in April 1943 as a satellite to RAF Tilstock, roughly eight and half miles away. Its job was training: getting crews through a hard, repetitive syllabus, often at night, often in weather that would make today’s flying clubs cancel.

The unit most closely tied to Sleap’s worst week was No. 81 Operational Training Unit, part of Bomber Command. 81 OTU operated Whitleys from the area, and later (during 1944) Sleap was used for Horsa glider training too. By November 1944, Wellingtons replaced the Whitleys for the remaining months of the war.

The Whitley itself was already sliding towards obsolescence by 1943. It had been a front-line bomber earlier in the war, but training units used it hard, and night exercises asked a lot of airframes and trainees alike. NAVEXes (night navigational exercises) were meant to build routine. In practice they could turn brittle: a dark runway, fatigue, heavy aircraft, a slight swing on take-off or landing, and suddenly there is not much time to recover.

RAF Sleap’s control tower sat at the centre of that system: a working building, not a monument. The words used are interchangeable: “control tower”, or “watch office”, but the idea is the same: the hub where flying control staff watched, timed, and managed aircraft movements.

The first Whitley: LA937, 26 August 1943

On 26 August 1943, Whitley V LA937 of 81 OTU took off from RAF Sleap at 20:50 for a routine night navigational exercise.

The details that survive in accessible summaries point to a nasty combination on return: a double engine failure as the aircraft touched down at the end of the night sortie, followed by a runway excursion and impact with the watch office/control building at RAF Sleap.

Accounts of the incident describe the Whitley (LA937) losing control on landing at night, running off the runway and crashing into the control tower. Three crew members in the front of the aircraft were killed, while others on board survived. The tower was damaged, but the station resumed normal operations the next day.

Some casualty listings tie the crash to the double engine failure and record named aircrew losses, including Sgt Thomas Reginald Armstrong (RCAF) and Fg Off Keith Nesbitt Laing (RCAF).

Even if you strip away everything except those hard points (date, aircraft serial, unit, night training, mechanical failure on landing, a building hit) the shape of it is familiar to anyone who has read through OTU losses. Training is meant to prevent operational deaths. In wartime, it creates its own.

And RAF Sleap carried on. It had to.

The second Whitley: BD257, 7 September 1943 – and the WAAFs in the control tower

Twelve days later on 7 September 1943, RAF Sleap suffered the accident that fixed the control tower in local memory and folklore.

Whitley BD257 (squadron code “N”) lost control on take-off, swung off the runway, and collided with the air traffic control tower/watch office. Accounts describe the aircraft bursting into flames on impact.

This time, the dead were not confined to the aircraft.

Two WAAFs on duty in the control tower were killed: Aircraftwoman 2nd Class Vera Hughes and Aircraftwoman 2nd Class Kitty Ffoulkes. Corporal N.W. Peate (male) was also killed in the building. Two other WAAFs were injured and survived. They were Leading Aircraftwoman. A B. Jowett, and Aircraftwoman H. Hall WAAF.

It’s worth pausing on the simple fact of where those women were. WAAFs served across roles that kept stations functioning including in operations rooms, communications, plotting, admin, meteorology, signals, and more. In the control tower at RAF Sleap they were not “near” flying operations; they were part of them. When the tower was hit, they were trapped in the place they were meant to keep safe for others.

On the Whitley, four of the five crew were killed. The fatalities were F/O. R W. Browne, F/O. E L. Ware RCAF, Sgt. W D. Kershaw, Sgt. E. Young. Sgt. S. Williams survived.

What it did to a station

It’s easy, with training accidents, to talk in the language of procedure and probability. A runway excursion. A swing. A loss of control. A building struck. But RAF stations were communities, and OTUs were built out of people under strain: instructors repeating the same lessons, pupils desperate not to wash out, groundcrew working long shifts, and flying control staff watching aircraft vanish into black skies then counting them home.

RAF Sleap resumed normal operations the day after the first control tower crash. That detail reads as both practical and chilling. The tower was damaged, men had died, and the airfield still flew.

After the second impact, it would have been impossible to keep the same emotional distance. Even if procedures changed, and it is reasonable to suspect that a serious internal review followed, as was standard after fatal accidents, readily available summaries don’t spell out what alterations were made locally.

What is clear is that the control tower became more than a working building at RAF Sleap. It became a scar you could point to.

After the war: the airfield keeps being used

RAF Sleap’s history did not end when the war did. Its later life helps explain why the tower stayed in public sight long enough for stories to gather.

During 1944 it served as a main training base for Horsa gliders, towed by Whitleys and Stirlings; later that year, Wellingtons replaced Whitleys in the training role.

Post-war, RAF Sleap continued as an active station with a major role in training air traffic controllers, with early jets among the visitors. By 1955, Shropshire Aero Club had been founded, and the site became a civilian airfield which is today described by the club as the only civilian licensed airfield remaining in Shropshire. There is also a small on-site museum run by volunteers.

So, the control tower did not vanish into a fenced-off ruin on a forgotten perimeter track. People kept coming here. Aircraft kept taking off and landing. That continuity matters, because it means the wartime past was never wholly sealed away. It sat alongside the ordinary business of flying.

The ghost stories: what people report, and what they might mean

“Haunted” can mean a lot of things. Sometimes it’s a literal claim: someone saw a figure, heard a voice, felt a touch. Sometimes it’s a shorthand: a place feels heavy because you know what happened there.

At RAF Sleap, the local legend is now openly acknowledged in modern heritage summaries, which link the haunting directly to the victims of those nights in 1943.

A great many of the specific modern anecdotes circulate through ghost-hunting groups and event listings rather than through formal history. That doesn’t make them worthless, but it does tell you what they are: contemporary stories told in the present tense, shaped for an audience that wants atmosphere.

One commonly repeated cluster of reports focuses on RAF Sleap’s control tower itself: footsteps on stairs or in empty rooms, doors opening and closing on their own, and the general sense of activity in spaces that are supposed to be still.

Another strand is looser, more like hangar talk. Aviation forums and local conversations sometimes mention RAF Sleap as haunted by a “woman pilot”. It’s a good example of how folklore moves: a place-name, a vague figure, and a story looking for a shape to settle into.

There are two cautions worth keeping in view.

First, the control tower deaths at RAF Sleap included two WAAFs on duty in the building, not a “woman pilot” in the usual sense. That doesn’t stop later retellings from blurring categories – WAAF becomes “woman aircrew”, then “woman pilot” – but it does matter if you’re trying to keep faith with the dead.

Second, the very features that make a derelict or semi-derelict tower eerie, such as wind through broken frames, settling concrete, sharp temperature shifts, the acoustics of empty rooms – also make it easy to misread ordinary sounds and sensations. None of that disproves anyone’s experience. It just means a historian has to separate the record of the crashes from the record of the stories told afterwards.

What’s more interesting, and more human, is how tightly the stories cling to the right object. RAF Sleap’s history of wartime tragedies did not happen in a distant field. They happened in the station’s nerve centre. The tower is where people watched aircraft come and go, where WAAFs and RAF personnel worked shifts, where routine was meant to hold the chaos at bay. When the tower itself was hit – twice – routine failed in the most physical way possible.

So, it makes sense that, in the post-war decades, the tower would become the focal point for talk about presence: footsteps on stairs, doors that move, the feeling that you are not alone. Those are the sorts of details people reach for when they try to put language around a place that holds more than it should.

Why WW2 airfield control towers become magnets for memory

WW2 airfields are full of vanishing things. Temporary huts. Dispersal pans reclaimed by scrub. Runway edges softened by grass. Even the big hangars are often rebuilt, repurposed, re-skinned.

WW2 airfield control towers are different. They are designed to be seen. They sit up, keep watch, and outlast the traffic that once justified them. If something violent happens to one, the damage feels like an affront: the watching eye struck blind.

At RAF Sleap, the “haunted” reputation is not a random gothic add-on. It grows from specific facts: two Whitleys from 81 OTU hitting the control tower/watch office during night training in 1943; the second incident killing WAAFs in the building (Vera Hughes and Kitty Ffoulkes); the airfield continuing in use long enough for those facts to be retold, simplified, embroidered, and passed on.

If you like wartime aviation folklore, RAF Sleap’s history offers the familiar ingredients: a surviving structure, a tight timeline of tragedy, and a community of visitors primed to feel something in an old tower at night. But the better story – because it stays honest – starts with the training station itself. Young aircrew learning to fly in darkness. Flying control staff doing their jobs. Two nights when the margin ran out. And the building left behind, still catching the weather, still catching the imagination.

Sleap doesn’t need exaggeration. The record is heavy enough.

jell