If you want a single aircraft that shows how fast the air war hardened in 1942, you could do worse than B-17F serial 41-24585, nose-named Wulfe Hound. It arrived at RAF Molesworth with the first wave of American heavy bombers, flew only a short early run of combat sorties, then arguably ended up serving the enemy more usefully than almost any bomber the Germans built themselves.

Most Flying Fortresses that failed to return from France or the Low Countries vanished into sea, fire, or scattered aluminium. Wulfe Hound was different. It came down in a field, crew alive, airframe damaged but not wrecked, and for the Luftwaffe that was a gift. It became a travelling classroom for fighter pilots, a test aircraft at Rechlin, and later part of the shadowy inventory of KG 200, the unit associated with special duties and the operation of captured aircraft.

Wulfe Hound B-17: Captured by the Luftwaffe

This is the story of how it happened, starting at RAF Molesworth.

The aircraft and its Molesworth identity

Wulfe Hound was a Boeing B-17F Flying Fortress, serial 41-24585, assigned to the 360th Bomb Squadron of the 303rd Bomb Group, the “Hell’s Angels”, based at RAF Molesworth. In squadron markings it carried the code PU-B.

That is the neat catalogue description. The operational reality in late 1942 was anything but neat. The Eighth Air Force in Britain was still learning the trade at full cost: how to assemble formations in English weather, how to hold position through icing and oxygen trouble, how to cope with gun malfunctions and fuel leaks, and what it meant to be jumped by fighters that came in fast and close. Even before a formation reached the enemy coast, aircraft were turning back with technical failures.

The B-17 named Wulfe Hound belonged to that improvised beginning. It did not have time to build up a long tally of missions. Its reputation comes from what happened when it did not come home.

12 December 1942: the mission that ended in a French hayfield

On 12 December 1942 the 303rd Bomb Group was tasked to bomb targets in northern France. Weather forced changes and decisions in the air, as it so often did in 1942–43. Wulfe Hound took off from Molesworth with a full crew of ten:

- 1st Lt Paul F. Flickenger Jr (pilot)

- 2nd Lt Jack E. Williams (co-pilot)

- 1st Lt Gilbert T. Schowalter (navigator)

- 2nd Lt Beverly R. Polk Jr (bombardier)

- T/Sgt William A. “Whit” Whitman (engineer)

- S/Sgt Iva Lee Fegette (radio operator)

- Sgt George N. Dillard (ball turret gunner)

- T/Sgt Frederick A. Hartung Jr (waist gunner)

- Sgt Norman P. Therrien (waist gunner)

- S/Sgt Kenneth J. Kurtenbach (tail gunner)

The formation met heavy fighter opposition. Wulfe Hound was hit, fell out of formation, and began to lose engines. There is a point in these accounts where a bomber stops being a bomber and becomes a very large aircraft simply trying to stay airborne. The crew jettisoned weight and tried to coax the remaining engines, but the direction of travel was now fixed: down.

Pilot Flickenger brought the aircraft in low, avoiding power lines, and put it down wheels-up in a hayfield. The ball turret was pointing down. The landing was hard, deliberate, and survivable. In the strange silence after impact, the crew found themselves in the middle of startled French civilians. Then the training took over. The crew smashed what they could of the radio and identification equipment and did as much damage to the aircraft as time allowed.

They could not destroy it.

Lieutenant Paul Flickenger later said he felt guilt due to the Wulfe Hound B-17 being the first of its type that the Luftwaffe was able to capture in working and flying condition. The crew reportedly attempted to destroy the B-17 Flying Fortress by stuffing a parachute into a fuel tank and then firing a flare pistol into it. But the Germans arrived before they could get a fire ignited. Flickenger became a POW but did manage to escape twice, being re-captured again on both occasions.

That is the hinge of the whole story. A damaged aircraft in a field is not automatically a write-off. If the enemy can secure it, guard it, and work on it without pressure, it can be recovered.

Escape lines and capture: the crew’s war splits in two

The immediate human story of Wulfe Hound is not one story but two.

Four of the crew were captured and became prisoners of war: Flickenger, Polk, Dillard, and Kurtenbach. Two of them were taken by the Gestapo later in December and interrogated before being moved into the POW system.

Six evaded and made it back to Allied hands via Spain: Williams, Schowalter, Whitman, Fegette, Hartung, and Therrien.

That simple split is easy to write down and hard to live through. It meant that a single crew, flying the same aircraft on the same day, ended up fighting two different wars: one behind wire, one on the run through occupied Europe. It also meant a second, quieter story unfolding around the crash site, because civilians who helped Allied airmen in occupied France were taking real risks.

Why the Luftwaffe cared: a captured Flying Fortress you could study properly

For the Luftwaffe, Wulfe Hound was not a trophy. It was a tool.

A B-17 Flying Fortress was a complicated system: armour, fuel, hydraulics, oxygen, electrical runs, turret mechanisms, gun positions, blind spots, and the practical question of what happened when it took hits. Intelligence officers could learn some of this from wrecks and prisoner interrogation. None of that compares to walking around a largely intact aircraft, testing equipment, and then flying it.

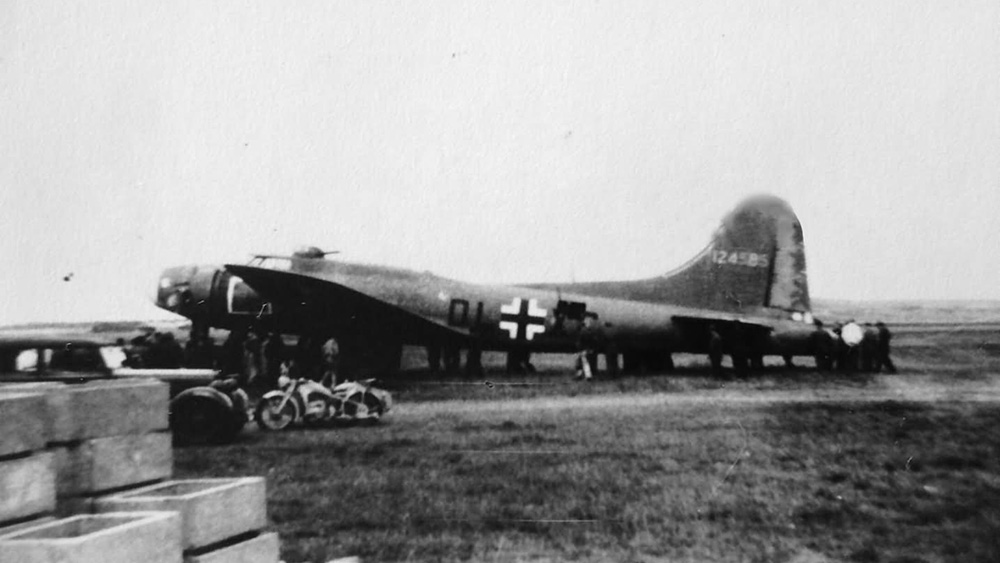

The Germans recovered Wulfe Hound and transported it to Leeuwarden in the Netherlands, where it was repaired to flying condition. It was painted in German markings and given the four-letter identification code DL+XC. The underside was painted yellow. The aircraft was then sent to Rechlin, the Luftwaffe’s main test and evaluation centre.

The first German flight is generally placed in March 1943. From that point on, Wulfe Hound became part of a structured programme: technical evaluation, handling checks, and the development of fighter tactics against the B-17.

This mattered for a simple reason. German fighter pilots could practise the geometry of attacking a Fortress against the real thing, not a diagram. They could see what angles were difficult to cover, where the guns bit hardest, and what the aircraft looked like from the positions they were trying to reach. It turned the B-17 from an idea into an object, and in air combat familiarity is an advantage.

A travelling classroom: what the captured B-17 aircraft was used for

Accounts of the aircraft’s German service emphasise two main uses.

The first was technical. Rechlin existed to test aircraft and systems. Flying a captured B-17 Flying Fortress allowed German evaluators to understand performance characteristics and the internal layout in a way that wreckage never could.

The second was tactical and instructional. The aircraft was used for demonstration and familiarisation, the sort of hands-on training that makes combat reports feel less theoretical. A captured bomber parked at an airfield also carried a psychological message: these aircraft can be brought down, and when they are brought down, they can be made to serve the other side.

There’s no romance in any of this, and there doesn’t need to be. The point is that the Germans were rational about captured equipment. If an intact B-17 was available, it would be exploited.

KG 200: the aircraft moves into the shadow inventory

In September 1943 Wulfe Hound was transferred to KG 200, the Luftwaffe unit associated with special duties and, among other things, the operation of captured aircraft.

This is the part of the story that attracts exaggeration. “Special operations” always does. It is safer to say only what the pattern supports: the aircraft’s role shifted from test and training work into a unit that handled unusual tasks, and captured aircraft were part of that toolkit.

One published account claims the aircraft was used on a clandestine transport mission carrying agents, operating out of the south of France. That kind of use fits the broader idea of why a special duties unit would want an Allied bomber in its inventory. But in this area, the paperwork is thin and claims should be treated as reported rather than fully documented.

The name: American nose art, not a German christening

One small correction is worth making because it crops up in retellings. The name Wulfe Hound and its nose art originated in USAAF service. The Germans inherited the name along with the aircraft, even if it was sometimes rendered in German spelling.

That matters because it keeps the aircraft rooted in its Molesworth identity. It began as an American bomber, named and flown by an American crew in the first hard months of the daylight war.

The end: damaged in 1945, and the irony of its final days

The Wulfe Hound B-17 Flying Fortress did not survive the war. The most persuasive end point places it at Oranienburg airfield in Germany in April 1945, where it was damaged during USAAF bombing and seen on reconnaissance imagery shortly afterwards.

There is an ugly neatness to that. The aircraft that had once carried the 303rd’s markings from RAF Molesworth ended up broken on a German airfield under American bombs.

Post-war recoveries of wreckage have been linked to the aircraft, including parts identified by serial number. In that sense it survives now the way many wartime machines survive: not as a whole, but as fragments, and as a paper trail that connects those fragments back to a specific aircraft and a specific day.

Why Wulfe Hound matters in the history of RAF Molesworth

Wulfe Hound is not the most famous aircraft to fly from Molesworth in the usual sense. It is, however, one of the most revealing.

It captures the precariousness of the Eighth Air Force’s early period at Molesworth, when missions were short in range but high in risk, and mechanical failures could stack up until a crew had to pick a field and hope.

It also shows that “loss” was not always clean disappearance. Sometimes an aircraft fell into enemy hands and carried on fighting, only in the wrong uniform.

And it reminds you that behind any operational summary there were ten men whose war forked sharply in a French hayfield: four into camps, six into the long business of evasion, with civilians making quiet choices that could have cost them their lives.

If you want a single line to carry it: Wulfe Hound is what happens when a bomber survives the crash but not the consequence.

If you want to know more about Wulfe Hound’s home airfield, read this history of RAF Molesworth.