On 20 December 1943, a young American pilot named Charlie Brown nursed his shattered B-17F Flying Fortress “Ye Olde Pub” away from the German city of Bremen. The bomber had been chewed up by flak and fighters. One engine was dead, another was failing, the nose was smashed, control surfaces were missing, the radio was out and most of the crew were wounded. One gunner lay dead at his station.

As the crippled B-17 limped alone over northern Germany, a Luftwaffe ace, Franz Stigler, scrambled in his Messerschmitt Bf 109. He was one victory away from the Knight’s Cross, a coveted combat decoration. The helpless B-17 should have been an easy kill.

Instead, Stigler made a different choice. Seeing the condition of the bomber and its crew, he refused to fire. He formed up alongside the American aircraft, escorted it past German guns and out over the North Sea, then saluted and turned away. Brown and his crew made it back to England.

The two men would not learn each other’s names, or meet, for nearly fifty years. When they finally did, they became as close as brothers.

The Charlie Brown and Franz Stigler incident

This is the full story of the Charlie Brown and Franz Stigler incident – an act of mercy in the middle of total war.

The air war over Bremen: winter 1943

By late 1943, the US Eighth Air Force was deep into its daylight bombing campaign over Nazi Germany. Targets like Bremen were ringed with flak batteries and defended by swarms of fighters. Losses on both sides were heavy; aircrews expected missions to be brutal.

On 20 December 1943, the target for the 379th Bomb Group was the Focke-Wulf 190 aircraft factory in Bremen which was a key producer of German fighters. The route would take the B-17 formations across the North Sea, over heavily defended coastal cities and deep into German airspace, all in mid-winter conditions at high altitude.

Bremen’s defences included around 250 anti-aircraft guns, backed by fighter units flying Messerschmitt Bf 109s and Focke-Wulf Fw 190s. Crews were warned in the briefing that they might face “hundreds” of enemy fighters.

Ye Olde Pub and her crew

Charlie Brown’s bomber that day was B-17F serial 42-3167, nicknamed “Ye Olde Pub”. Built by Douglas, it flew with the 527th Bomb Squadron, 379th Bomb Group based at RAF Kimbolton in Cambridgeshire, England. This was the first time 21-year-old 2nd Lt Charles L. “Charlie” Brown flew as aircraft commander on a combat mission.

Ye Olde Pub carried a crew of ten:

- 2nd Lt Charlie Brown – pilot and aircraft commander

- 2nd Lt Spencer “Pinky” Luke – co-pilot

- 2nd Lt Al Sadok – navigator

- 2nd Lt Robert Hull – bombardier

- T/Sgt Dick Pechout – top turret gunner / engineer

- T/Sgt Bertrund “Frenchy” Coulombe – radio operator

- S/Sgt Lloyd Jennings – waist gunner

- S/Sgt Hugh Eckenrode – tail gunner

- S/Sgt Alex Yelesanko – waist gunner

- S/Sgt Sam Blackford – ball turret gunner

In the pre-mission briefing, Brown’s crew were initially assigned a vulnerable “Purple Heart Corner” position at the edge of the formation, where German fighters liked to pick off stragglers. When three other bombers had to turn back with mechanical problems, Ye Olde Pub was moved up to the front of the group – a position that would soon prove equally dangerous.

Into Bremen: flak and fighters

The bomber stream crossed the German coast late in the morning after leaving RAF Kimbolton. At around 11:30, as Ye Olde Pub neared the target at 27,000 feet in temperatures around –60°C, black puffs of flak burst around the formation. Charlie Brown later likened the exploding shells to “fantastically beautiful black orchids with vivid crimson centers” – beauty masking lethal intent.

Within minutes, the B-17 was hit repeatedly:

- A flak shell shattered the Plexiglas nose, blasting it off and sending shards back over the windshield.

- Engine no. 2 was knocked out entirely.

- Engine no. 4 was damaged and had to be throttled back to avoid over speeding.

- The oxygen system, hydraulics and electrics were all hit; heating wires in the crew’s suits failed.

Flying with reduced power, Brown could not keep formation. Ye Olde Pub began to fall back, becoming a “straggler” which was exactly the position the Luftwaffe fighters hunted.

Over Bremen and on the return leg, waves of German fighters pounced: Bf 109s and Fw 190s from Jagdgeschwader 11 and other units. For more than ten minutes they hammered the isolated B-17.

The damage mounted:

- Engine no. 3 was hit and reduced to half power.

- Half the rudder and much of the left elevator were blown away.

- The radio was destroyed.

- A large hole was torn in the fuselage.

- Of the bomber’s eleven defensive guns, all but three jammed or failed.

The crew paid a terrible price. Tail gunner Hugh Eckenrode was killed, decapitated by a cannon shell that tore through the rear of the aircraft. Waist gunner Alex Yelesanko was critically wounded in the leg by shrapnel. Top-turret engineer Dick Pechout was hit in the eye. Ball turret gunner Sam Blackford’s feet were badly frostbitten when his heated boots failed. Charlie Brown himself was wounded in the right shoulder. The morphine syrettes for first aid were frozen solid.

Under that storm of fire, Ye Olde Pub was effectively defenceless and barely controllable.

A dying bomber over Germany

At one point the battered B-17 went into a steep dive, dropping thousands of feet. Brown lost consciousness as his oxygen system failed; the bomber only levelled out when it descended into thicker air near 1,000 metres. When he came to, the aircraft was still somehow flying, but almost everything that could be wrong, was.

The crew now faced a grim choice. They could attempt an emergency landing in Germany and face captivity as prisoners of war or try to coax their wrecked aircraft back across enemy territory and the North Sea to England.

Those still able to move refused to surrender. They would try for home.

With only one fully functioning engine and one halfway useful, control surfaces shredded and half the crew wounded or unconscious, Brown pointed the nose northwest. Ye Olde Pub, alone and limping, headed roughly toward the coast.

Down below lay airfields like Oldenburg – and men of the Luftwaffe whose job was to finish off stragglers exactly like this one.

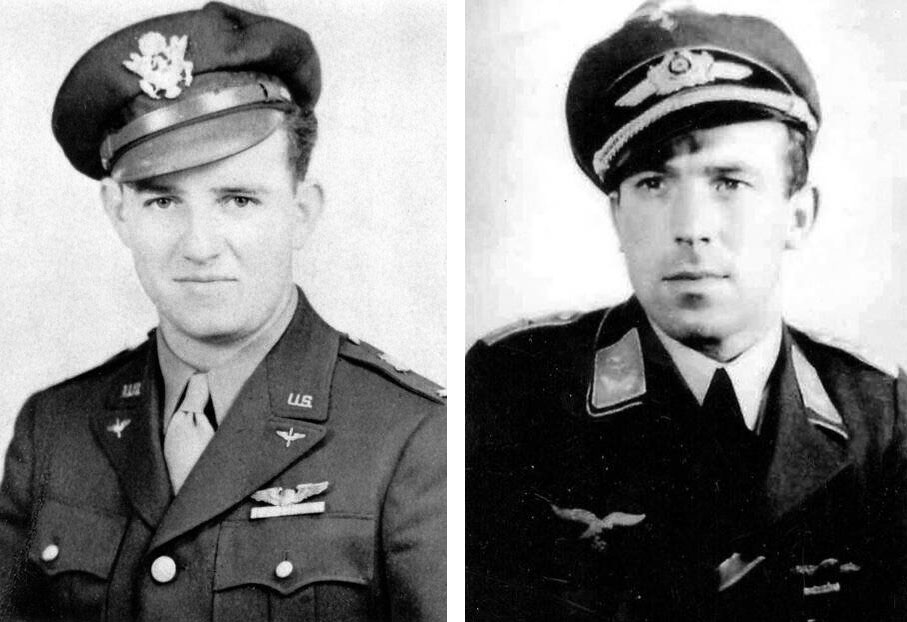

Franz Stigler: the Luftwaffe ace with his own code

On the ground near Bremen that day was Oberleutnant Franz Stigler, an experienced fighter pilot of Jagdgeschwader 27. He’d fought in North Africa and Italy, flown more than 400 combat missions, and claimed around 27–28 aerial victories. He had also been shot down multiple times and lost his brother in the war.

Stigler belonged to a generation of Luftwaffe pilots trained before and during the early war years, when some officers still spoke of an old-fashioned “knightly” code of conduct in the air. His commanding officer, Gustav Rödel, had impressed on him that there were limits to what a fighter pilot should do, even against an enemy. Rödel’s advice, as Stigler later recalled, was:

“You follow the rules of war for you – not for your enemy. You fight by rules to keep your humanity.”

On 20 December 1943, Stigler was one victory short of qualifying for the Knight’s Cross. Shooting down another B-17 would have earned him both a medal and prestige.

When the crippled Ye Olde Pub flew low over his airfield, leaving a trail of smoke, it looked like an ideal opportunity. Ground control authorised him to scramble. He took off in his Bf 109G-6 to intercept.

“It would be murder”: the encounter over Oldenburg

Stigler climbed to intercept and quickly spotted the limping B-17. As he approached from behind, he was puzzled. There was no defensive fire. He eased closer.

What he saw stunned him. The tail of the bomber was shredded. The tail gunner’s position was smashed open, the gunner motionless. The rear fuselage had gaping holes. The rudder was half-gone. The nose was missing. The aircraft was peppered with hundreds of bullet and shell holes.

Looking into the fuselage as he drew level, Stigler could see wounded men being tended where they lay. In Adam Makos’s account “A Higher Call” and in later interviews, Stigler described thinking that these men were effectively already in their parachutes – helpless. Shooting them down would not be combat; it would be execution.

He moved up alongside the cockpit so close that Brown and co-pilot Pinky Luke could see his face. Inside Ye Olde Pub, panic flared. A German fighter three feet from the wingtip could finish them with a short burst. Luke reportedly said, “My God, this is a nightmare.”

Instead of firing, the German pilot looked at them and nodded.

Franz Stigler tried to signal options by hand gestures and flying motions: land at a nearby German airfield and surrender or turn north toward neutral Sweden where the crew could receive medical care and be interned. Charlie Brown and his men, exhausted, wounded and unable to interpret his intentions, refused. They kept heading for the North Sea.

Realising they were determined to try for England, Stigler made a new decision. He would escort the American bomber as far as he could.

Escort to the sea

Flying close alongside Ye Olde Pub, Stigler shepherded the bomber across German-held territory. From some angles, gunners and anti-aircraft crews on the ground would see a German fighter flying in formation with a B-17 and assume it was a captured or disguised aircraft or at least hesitate to fire while they worked out what was going on.

For Franz Stigler, this was not only an act of mercy but a personal risk. If any superior had learned that he had deliberately spared an enemy aircraft – particularly one that had just bombed a German city – he could have faced court-martial and possibly execution. Nazi Germany did not look kindly on perceived softness toward the enemy.

Near the German coast, now approaching the edge of effective flak coverage, Stigler judged that the bomber was as safe as he could make it. He slid into position off Brown’s left wing, looked across the short gap of air and raised his hand in salute. Then he peeled away, turning back toward Germany, leaving the battered B-17 to cross the sea alone.

“Good luck,” he is later quoted as saying to himself. “You’re in God’s hands now.”

Crossing the North Sea

Brown did not fully understand what had just happened. Still half expecting a final burst of cannon fire from behind, he kept his remaining guns trained on the departing fighter until it disappeared. Then he turned his full attention to keeping Ye Olde Pub in the air.

The flight across the North Sea was a slow, tense crawl. With two engines at reduced power, damaged control surfaces and a shot-up airframe, the bomber could barely hold altitude. Fuel was low. If a headwind picked up or an engine failed entirely, the crew would have to ditch in icy winter waters.

Somehow, they made it. Ye Olde Pub reached the English coast and diverted to RAF Seething in Norfolk, home of the 448th Bomb Group. Brown put the aircraft down in a rough but successful landing. The surviving crew were pulled from the bomber and rushed to medical care.

Photographs taken afterwards show a B-17 so badly damaged that many later viewers could not believe it had flown, let alone crossed enemy territory and a sea. Ye Olde Pub never returned to combat; she was sent back to the United States in 1944 and scrapped after the war.

Silence, reports and orders

At debriefing, Brown told his superiors about the German fighter that had appeared, refused to shoot and then escorted them away. The reaction was cautious. In a war that depended on demonising the enemy to keep men fighting, a story of a chivalrous Luftwaffe pilot letting a bomber go was not something commanders were keen to publicise.

Brown was reportedly advised to keep quiet about the incident. The episode was not officially investigated and did not appear in wartime propaganda.

The air war moved on. Charlie Brown completed his tour, eventually leaving the service, returning in the new US Air Force in 1949 and later serving as a Foreign Service officer in Laos and Vietnam.

Franz Stigler, for his part, survived the rest of the war, later flying one of Germany’s first operational jet fighters, the Messerschmitt Me 262, with Jagdverband 44. After the war he emigrated to Canada in 1953, becoming a successful businessman in Vancouver.

Neither man knew the other’s name. Neither knew for certain whether the other had survived.

Post-war shadows and the search for the unknown enemy

Like many veterans, Brown carried the war with him in memories and nightmares. His daughter later recalled that he would sometimes wake in a cold sweat. In some dreams, there was no act of mercy; the German fighter finished the job and the bomber went down.

In 1986, long after retirement, Brown was invited to speak at a “Gathering of Eagles” event at Maxwell Air Force Base, an annual meeting of prominent aviators. Asked about his most memorable mission, he decided to recount the strange story of the German fighter that had spared his crew.

The experience spurred him to take on a new mission: find the unknown pilot who had held his life in his sights and chosen not to take it.

Brown wrote to US and German archives, searched wartime records and contacted veterans’ organisations, but with little success. Finally, he placed a short account of the incident in a newsletter for former Luftwaffe pilots, asking if anyone recognised the story.

On 18 January 1990, a letter arrived at Brown’s home in Florida.

“Dear Charles,” it began. The writer explained that he had seen the newsletter article and believed he was the pilot in question. He described the encounter over northern Germany, the damaged B-17, the salute and the escort to the sea. He had long wondered whether the bomber had made it. To learn that the crew survived, he wrote, filled him with joy.

The letter was signed: Franz Stigler.

Meeting at last: from enemies to brothers

Brown wasted no time. He called directory assistance in Vancouver, got a number for Franz Stigler and dialled. When the man on the other end confirmed who he was, Brown reportedly blurted, “My God, it’s you!” and broke down in tears.

That summer, they agreed to meet in person at a hotel in Florida. A friend filmed their first reunion: two elderly men in shirts and caps, approaching each other in a lobby. They paused for a moment, then embraced, laughing and crying.

Over the following days they compared memories from that day over Bremen, piecing together details from both cockpits. They also talked at length about their wartime experiences and how the incident had stayed with them over the decades.

When a reporter later asked Stigler what he thought of Brown, his jaw tightened and he fought back tears before saying, in accented English, “I love you, Charlie.”

From that point on, they regarded each other as family. They visited often, spent holidays together, attended reunions and spoke at public events about their story. Brown’s children called Stigler “Uncle Franz”.

Between 1990 and 2008, their friendship lasted until the end of their lives. Stigler died in March 2008 in Canada; Brown died a few months later, in November, in the United States.

A Higher Call and the public story

For decades, the story of the Charlie Brown and Franz Stigler incident was known only to a small circle of veterans and friends. That changed with the publication of Adam Makos’s book “A Higher Call: An Incredible True Story of Combat and Chivalry in the War-Torn Skies of World War II” in 2012.

Makos spent years interviewing Charlie Brown, Franz Stigler, their families and fellow airmen about the incident. The book placed their encounter within the wider context of the air war, the Nazi regime, and the personal histories of both men. It presented Stigler not as a simple hero, but as a complex figure: a skilled pilot who served a brutal regime yet clung to his own moral compass.

The story reached new audiences through documentaries, magazine articles and even music. Swedish metal band Sabaton wrote a song about the Franz Stigler and Charlie Brown incident, “No Bullets Fly”, on their 2014 album “Heroes”, narrating the mission and the moment of mercy.

In later years, a preserved B-17 was repainted as Ye Olde Pub and flown at airshows, keeping the visual memory of the aircraft alive.

Brown and his surviving crew were eventually recognised with decorations: in 2008, at Brown’s request, the B-17 crew received the Silver Star, while Brown himself was awarded the Air Force Cross. In 1993, Stigler was presented with the “Star of Peace” by a European combatants’ federation, honouring his act of mercy.

Chivalry in total war

The Charlie Brown and Franz Stigler incident stands out because it runs so strongly against the grain of the time. The strategic bombing campaign over Europe was a ruthless business; crews on both sides saw cities burn and friends die. Air warfare was increasingly industrialised and impersonal.

Against that backdrop, one fighter pilot’s decision not to press his advantage – and instead to protect his enemy – has come to symbolise the idea that even in total war, individual choices still matter.

For Stigler, sparing the B-17 risked his career and possibly his life, but preserved something more important: his sense of himself as a human being, not just a weapon. For Brown and his crew, the act meant survival – and, decades later, a friendship that helped both men make sense of what they had lived through.

As Makos and others have argued, the story does not erase the horrors of the war or redeem the regime Stigler fought for. What it does is show that compassion can appear in the unlikeliest places, even between enemies.

Image credits:

- Header image: The Guardian © Nicolas Trudgian