On 17 December 1940 a Bristol Beaufighter came back towards RAF Debden after a training sortie but failed to reach the runway. The aircraft went down over farmland in Essex in the space of seconds. Two men who had already carried their share of the Battle of Britain were killed, not by the enemy, but by the hard, everyday danger of learning to fight at night.

The crash of Bristol Beaufighter (R20996)

Pilot Officer Frederick George Nightingale

Frederick George Nightingale was 26. He had not come into the RAF as a pilot. Born in Reigate in 1915, he enlisted in November 1934 as an aircraft hand, working on aircraft rather than flying them. Over the next few years he worked his way up, applied for pilot training, and was accepted, remustering as an under-training pilot at the end of 1938.

He completed his course at No. 3 Flying Training School at South Cerney between March and October 1939, and went straight to No. 219 (Mysore) Squadron.

By the summer of 1940, 219 Squadron was operating Blenheims as night fighters from northern bases such as Catterick. As the battle developed, the squadron’s work and its locations shifted south, into the growing pressure of night air defence. Nightingale soon found himself in action. On 15 August 1940, over the Scarborough area, he damaged a Junkers Ju 88. In October 1940 he was commissioned from the ranks, a ground tradesman turned officer in a remarkably short, intense run.

Sergeant George Mennie Leslie

His observer on the last flight, Sergeant George Mennie Leslie, came from a different place. He was born in Aberdeen on 27 March 1911, son of Andrew and Mary Ann Leslie. In 1937 he married Grace Duncan Milne at St Machar’s Cathedral. That matters because it fixes him as someone with a settled civilian life before his RAF enlistment.

He joined in June 1940 as an aircrafthand but was soon retrained as a radar operator, one of the new specialists needed for Airborne Interception radar in night fighters. After training he was posted to 219 Squadron on 2 August 1940, at the point when regular night work was beginning to bite.

By late 1940 the two of them, a young but already operational pilot and a newly trained radar operator, were part of the RAF’s attempt to make night fighting work at scale.

RAF Debden and the new equipment war

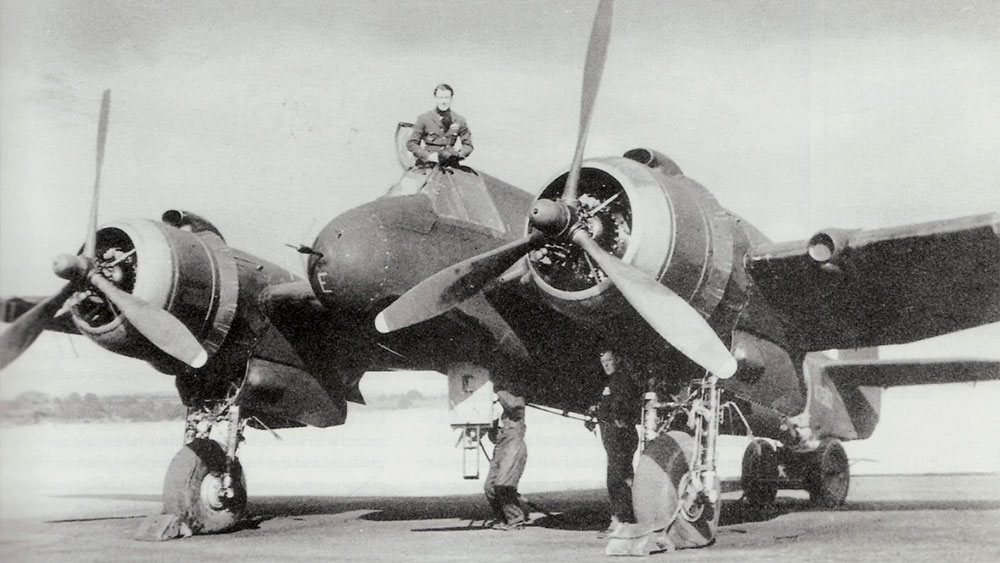

In the autumn and early winter of 1940, 219 Squadron converted from Blenheims to the Bristol Beaufighter Mk IF. The Beaufighter brought speed and heavy armament, and it was among the first fighters to carry AI Mk IV radar in significant numbers.

Detachments operated from airfields including RAF Debden in Essex, a busy fighter station east of Saffron Walden which hosted multiple squadrons during and after the Battle of Britain.

The radar itself was still new and awkward. Crews were learning to fly on instruments, interpret a glowing tube in the dark, and turn that into an interception. Training sorties combined instrument work, radar practice and formation flying, and they carried their own risks. There are records of other 219 Squadron personnel being detached to Debden for AI courses in December 1940, which fits the broader picture of a unit converting and training hard.

It was in that atmosphere that Beaufighter R2096 went up on 17 December.

The Beaufighter crash at Smiths Green Farm

Beaufighter Mk IF R2096 of 219 (Mysore) Squadron took off from RAF Debden on 17 December 1940 for a training flight. On the return, one engine failed. The aircraft was in the approach phase when it “spun in” and crashed at Smiths Green Farm near the station. The Beaufighter was destroyed and both crewmen were killed.

Not their first close call

For Nightingale, it was a bleak irony. A year earlier, on 1 December 1939, he had survived an engine failure in an Avro Tutor, K3433. He forced-landed in a field near Grantham; the aircraft stalled and was written off, but he and his passenger escaped unhurt.

He then lived through the summer of 1940 as a night-fighter pilot, damaging an enemy bomber, only to be killed a few months later on a training flight within sight of his base.

Leslie’s RAF service was shorter still. He enlisted in June 1940, retrained into a specialist role, and died in December the same year. A civilian life in Aberdeen, then a few compressed months learning a brand-new kind of air war, and then the end of it.

The unseen cost

This is not a combat story. There is no raid intercepted, no victory claim, no dramatic last-minute escape. It sits in the category that wartime histories often skate over: the cost of training, conversion, and new equipment.

By late 1940 Britain was trying to weld together AI radar, heavy fighters like the Beaufighter, and evolving ground control tactics into something reliable. The system was starting to work, but it was not forgiving. Training demanded flying in darkness, on instruments, while operating unfamiliar kit and absorbing instructions at speed. Mechanical failures and human limits did the rest.

Nightingale and Leslie were part of that effort. Their deaths on 17 December 1940 belong to the quiet side of the air war, where progress was measured not just in sorties and results, but in lives lost before the enemy even came into view. The surviving summaries do not tell us what was said in the cockpit, or how close they came to saving it. They do not need to. The facts we have are stark enough: one engine out on approach, a spin over an Essex farm, and two graves in Saffron Walden Cemetery that mark the price of learning to fight at night.